In case there wasn't enough to worry about here on Earth in terms of climate change, an artificial intelligence takeover, or countries nuking each other, none of that will matter if our third rock from the Sun is destroyed by some intergalactic threat. We're not just talking about little green dudes invading us or 'God of Chaos' asteroids, but what about supermassive black holes?

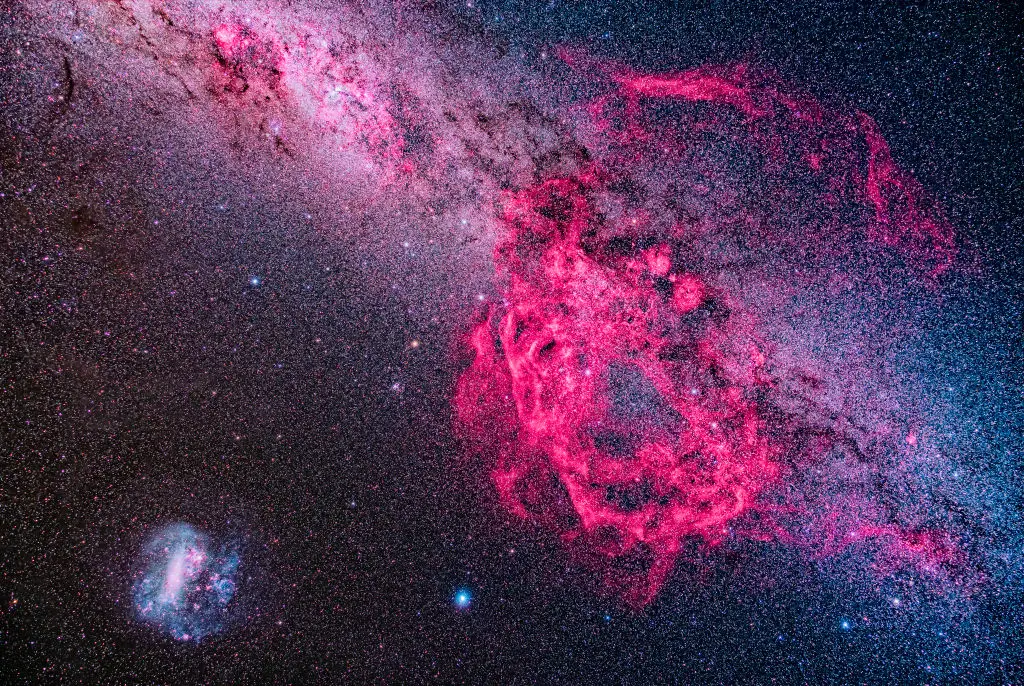

As reported by the New Scientist, a supermassive black hole lurking in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) could be responsible for nine stars that are currently hurtling around our galaxy. The Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics' Jiwon Jesse Han suggests that the black hole inside the LMC could have a mass that is 600,000 times greater than that of the Sun.

In contrast, one at the center of the Milky Way has a mass around four million times that of the Sun.

Advert

Remembering that the LMC is on an ever-closing loop that will one day collide with our galaxy, it's only a matter of time until Earth is in danger of being swallowed by this monster from the stars (thankfully, we’ll all be long gone by then).

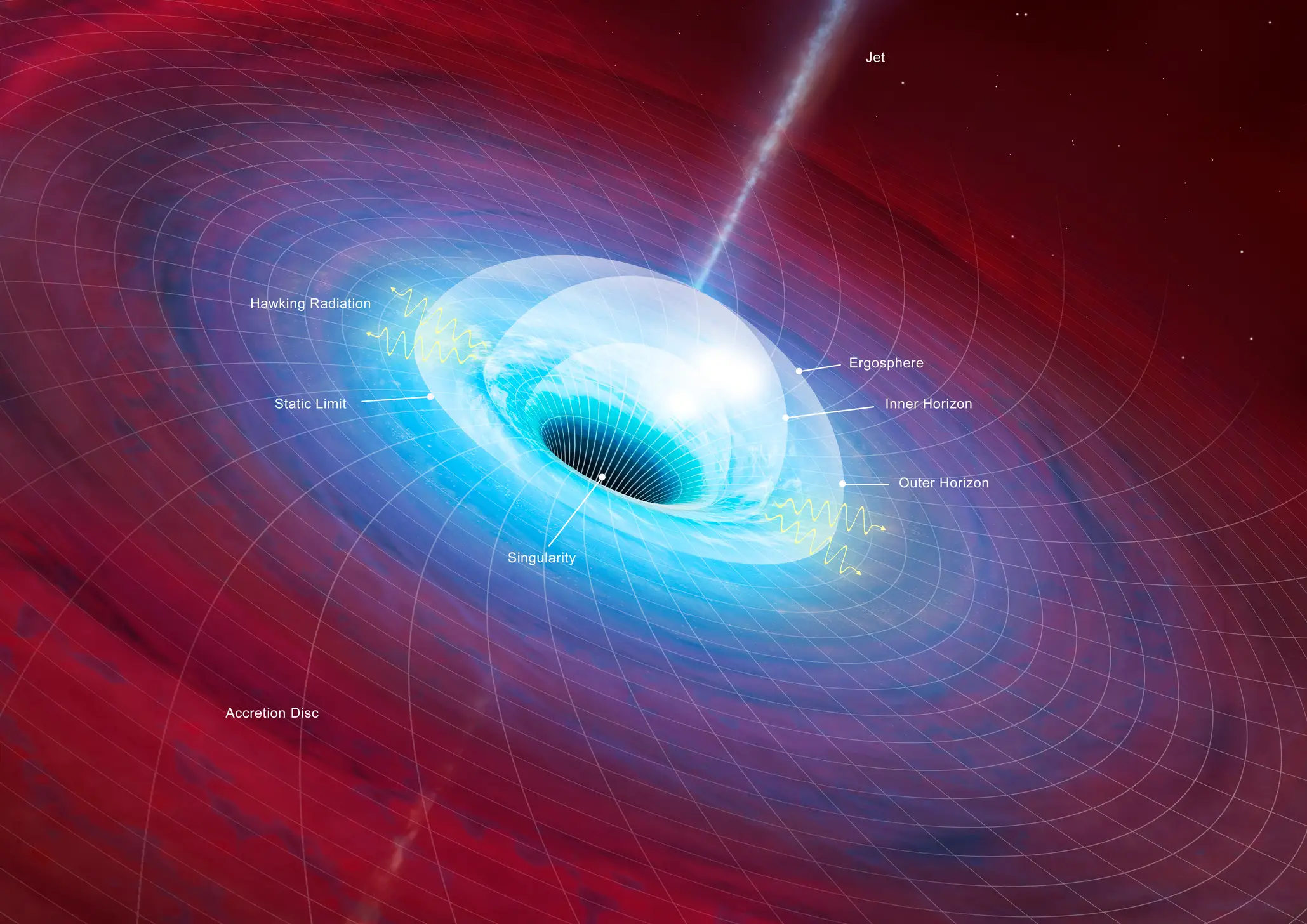

Han and the team discovered the existence of the supermassive black hole by analyzing so-called hypervelocity stars that travel at more than 500 kilometers per second. According to Emily Hunt at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, "It’s really impossible to explain those high speeds with supernova ejections," meaning these speeds are reached by gravitationally slingshotting around a supermassive black hole.

Although research is yet to be peer-reviewed, it's thought that around half of the Milky Way's hypervelocity stars could be traced back to the LMC's supermassive black hole. Nine hypervelocity stars have been potentially tracked to a region in the northern sky that's referred to as Leo Overdensity.

Championing the research, Han explained: "We can rewind the paths of these stars to see where they come from, and they track directly back to the LMC."

Despite previous speculation that black holes are hiding out in dwarf galaxies, it's so far been 'impossible' to prove. While Han says, "They’re too far away to image," the LMC's relative closeness of some 163,000 light-years away means we might be able to see stars orbiting it: "I think I know where to point, but I’m not going to give away the coordinates just yet."

Further study is needed, but this supermassive black hole is extremely rare because it has a mass that is less than a million times that of the Sun. If it can be proved, it's hoped that it will give scientists a better understanding of how black holes from from masses the size of stars to behemoths that have the potential to consume whole star systems.

Han concluded: "One of the outstanding questions in astronomy is how did supermassive black holes begin. The dwarf galaxy supermassive black hole population is a good tracer of the initial seed mechanisms. And this would be the first [direct] detection of a supermassive black hole in a dwarf galaxy."

While work is ongoing, Han still thinks that even a powerful black hole observatory like the Event Horizon Telescope might not be able to capture this rarity in action.