Scientists have unearthed more than 1,700 ancient viral species inside a glacier in the Himalayas.

They are now racing to secure ice cores as global warming continues to cause ice melts around the world and the public fears it could release potentially dangerous pathogens.

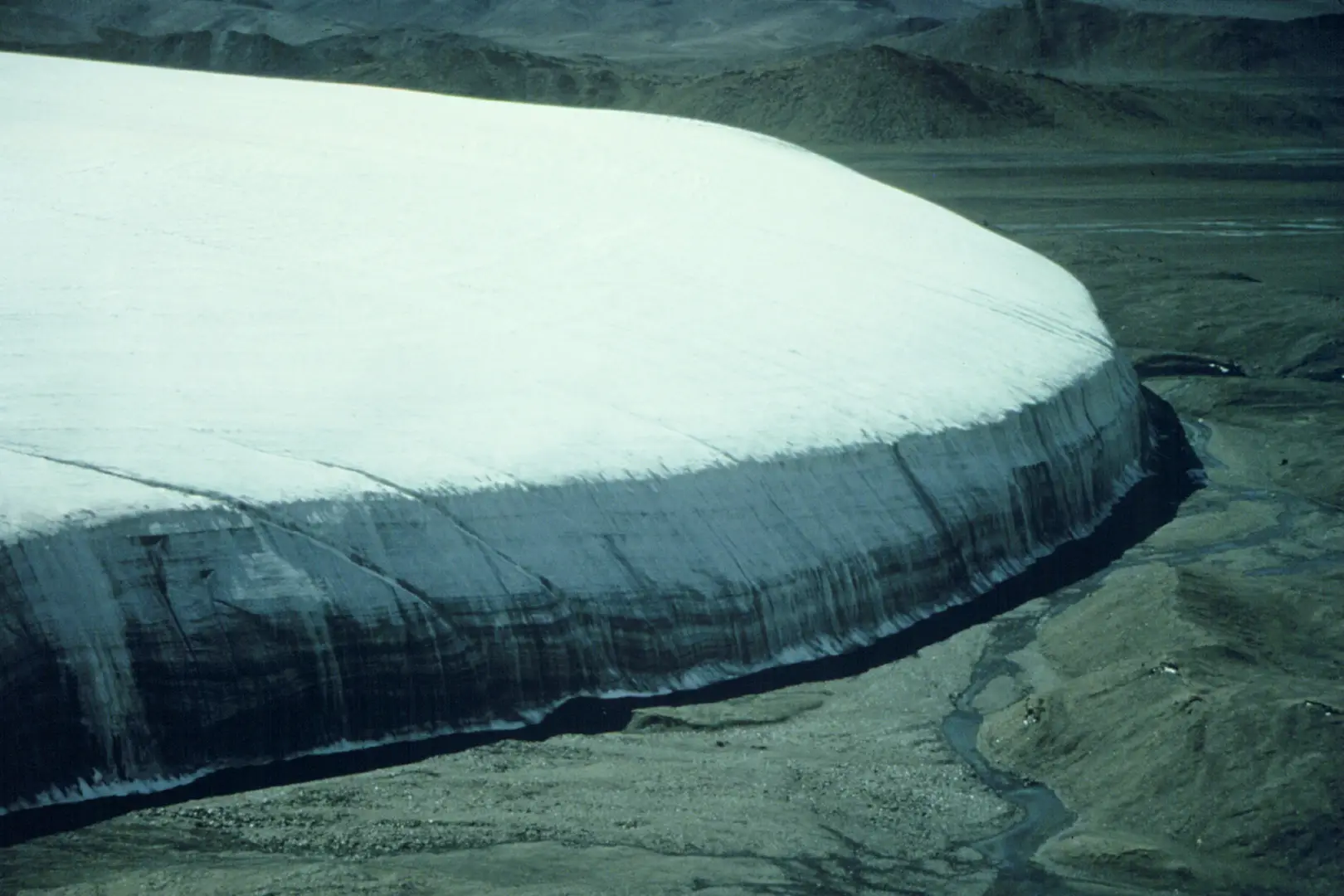

In 2015, an international team of researchers ventured to the Guliya Glacier on the Tibetan Plateau in the Himalayas to collect ice cores.

Advert

Trapped inside an 1,000-foot-long ice core were more than 1,700 species of virus, most of which have never been seen before. Some date back as far as 41,000 years ago and have survived three shifts from cold to warm climates.

The discovery has sparked some concern from the public.

Melting permafrost at other locations around the world have previously released deadly pathogens into the air.

In 2016, spores of anthrax escaped from an animal carcass when the Siberian permafrost it had been frozen in for 75 years melted.

Dozens were hospitalized and one child died as a result.

So when rapper-turned-actor Ludacris posted a video of himself on social media drinking meltwater from an Alaskan glacier, people were understandably a little bit worried.

Fortunately, a glaciologist has since stated that water from a glacial melt is 'about the cleanest water you'll ever get.'

As for the viruses in the Himalayan ice core, researchers have said that none pose a threat to human health. This is because they can only infect single-cell organisms and bacteria. Humans, animals and even plants are all safe.

But they're still important for study, providing us with a snapshot of how viruses have adapted to changes in climate over time.

The team of researchers led by Ohio State University drilled over 1,000 feet into the Guliya Glacier and retrieved nine segments of ice core, each representing a different time period ranging from 160 to 41,000 years ago.

"These time horizons span three major cold-to-warm cycles, providing a unique opportunity to observe how viral communities have changed in response to different climatic conditions," said ZhiPing Zhong, a paleoclimatologist at Ohio State University and lead author of the study.

DNA extracted from these segments was then analyzed, giving them insight into the Earth's deep climatic history as well as what the future could hold.

"By studying these ancient viruses, we gain valuable insights into viral response to past climate changes, which could enhance our understanding of viral adaptation in the context of ongoing global climate change."