Archaeologists in Spain have discovered a unique tablet with ancient drawings of Tartessian battle scenes and a never-seen-before alphabet.

The artworks were found during ongoing excavations at Casas del Turuñuelo, an ancient Tartessian site in southwestern Spain.

The Tartessos people were an ancient civilisation that first settled in the Iberian peninsula around the eighth century B.C. but mysteriously vanished by the fourth century B.C. - with only a minimal amount of artefacts of their culture scattered around.

The unearthed tablet has an alphabetical 'sequence of 21 signs' in Paleo-Hispanic script carved around its edges, according to the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC).

Advert

However, a piece of the tablet is missing, so researchers can only guess which letters might be absent from the sequence.

The Tartessos people were known for their complex writing system however, this is only the third piece of evidence that shows the Tartessos people had their own alphabet.

'At least [six] signs would have been lost in the split area of the piece, but if it were completely symmetrical and the signs completely occupied three of the four sides of the plate, it could reach 32 signs,' said Joan Ferrer i Jané, a researcher in paleo-hispanic philology (the study of language development) at the University of Barcelona.

'It is a shame that the final part of the alphabet has been lost since […] that is where the most pronounced differences tend to be.'

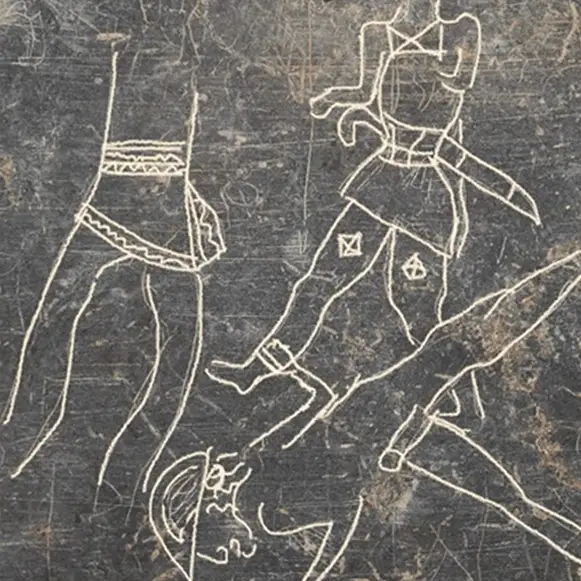

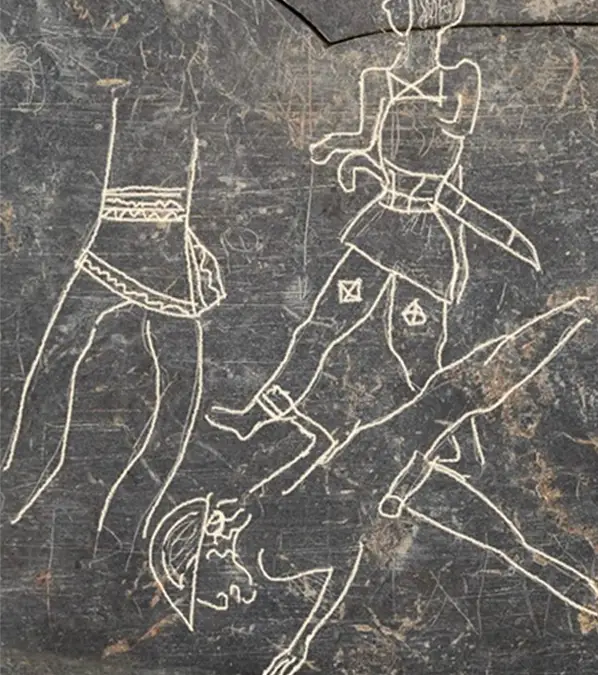

The slate measures 8 inches (20 centimetres) long and also features engravings of three warriors in battle.

Researchers believe these sketches were likely practice drawings that the artist used to perfect their skills before engraving similar designs onto permanent canvases like gold, ivory, or wood.

According to Fox News, the slab dates back to around 600 BC, making it about 400 years older than Egypt’s famous Rosetta Stone.

'This discovery represents a unique example in peninsular archeology and brings us closer to the knowledge of the artisanal processes in Tartessos, invisible until now,' added Esther Rodríguez González, study co-leader and an archaeologist at the Institute of Archeology of Mérida.

'At the same time, it allows us to complete our knowledge about the clothing, weapons or headdresses of the characters represented.'